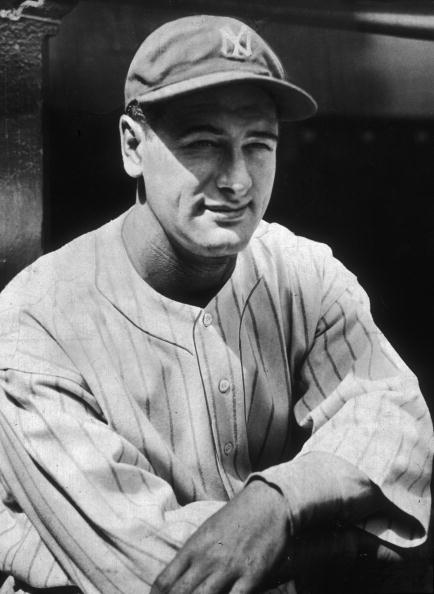

If you asked fans that are new to the game of baseball who Lou Gehrig was, many would answer “There’s a disease named after him.” Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, or ALS, is a hideous disease that robs its victims of their body while their mind stays sharp as a tack. It’s a particularly cruel disease in a sea of end-of-life maladies and what took Gehrig’s life.

Many younger fans may only know of Gehrig’s iron man streak of 2,130 consecutive games that was surpassed by Baltimore’s Cal Ripken Jr. nearly six decades later. But, Gehrig, the New York Yankees first baseman, was much more of a ballplayer than just a streak record holder. His offensive production is even more remarkable when you consider that he played in so many consecutive games. Gehrig was part of one of the greatest teams of all-time – the Murderer’s Row squad of 1927 – and other teams that weren’t too shabby either.

It didn’t matter if the Yankees were home or away. It didn’t matter if it was a right-hander or a southpaw on the mound. In all likelihood, Gehrig was going to crush the baseball no matter what. He batted cleanup for the majority of his career. That meant Babe Ruth hit in front of him for the dozen years they played together (for the uninitiated, baseball numbers were originally assigned by your spot in the batting order – hence, Ruth No. 3, Gehrig No. 4, etc.). If pitchers worked around Ruth, Gehrig would make them pay for it.

Gehrig the Engineer

Gehrig was not a typical baseball player of his era. Not many players went to college, but Gehrig had a football scholarship to Columbia University. The native New Yorker’s plan was to study engineering while continuing to play football and baseball. Legend has it that New York Giants manager John McGraw told Gehrig he should play in a pro baseball league during the Summer before he started his college education.

Gehrig played in the league under an assumed name but he was eventually caught and was banned from playing freshman college baseball. But, a year later, on the same day Babe Ruth christened the brand new Yankee Stadium with its first home run, Gehrig struck out 17 batters in a start for Columbia. Two months later, Gehrig made his Yankees debut.

Ruthian Exploits

By the time Lou Gehrig joined the Yankees, Babe Ruth was already an established star. He was also larger than life. That was a plus for Gehrig and his teammates since Ruth sucked all the air out of the room. Intentional or not, it relieved his teammates of some of the pressure placed upon them. If Gehrig felt any pressure, he didn’t show it.

“I’m not a headline guy. I know that as long as I was following Ruth to the plate I could have stood on my head and no one would have known the difference.” – Lou Gehrig on his teammate, Babe Ruth.

The former Columbia student played in just 23 games during his first two years in the Majors. In 1923, he played 59 games for Hartford in the class ‘A’ Eastern League and produced Ruthian results…24 home runs in just 227 at-bats, to be exact. His second year in Hartford produced a .360 batting average, 37 home runs, 4o doubles, and 13 triples in 137 games.

You’ve been “Wally Pipped”

Gehrig’s first full season in the Majors was in 1925 and earned Wally Pipp a dubious distinction. One day when the first baseman wasn’t feeling well, Gehrig replaced him in the lineup and he never looked back. (Another account that isn’t as dramatic is that Gehrig was put in the lineup because Pipp was in a slump.) Pipp’s name became synonymous with losing out on something due to unfortunate timing. But, truth be told, Gehrig would have taken his spot in short order anyway.

Not many people realize that Pipp was no slouch at the plate either. He finished 14th in the AL MVP race in 1924 after he produced 58 extra-base hits, knocked in 109 runs, and walked more times (51) than he struck out (36). Once Gehrig got a chokehold on the first base job, however, Pipp found himself in Cincinnati for the final three years of a 15-year career.

The Iron Bat

In a 126-game rookie season, Gehrig showed a small sampling of what he was capable of. He hit 20 home runs, added 23 doubles and 10 triples, and tallied 68 RBI. His split of .295/.365/.531 contributed to a 24th place finish in the AL MVP vote.

Gehrig followed that with a very good season and then in 1927, he and the Yankees completely dismantled American League pitching. After hitting 26 home runs in his 281 previous career games, Gehrig slugged 47 in 155 games. He drove in an unreal 173 runs, scored 149, collected 281 hits, legged out 52 doubles and 18 triples, and batted a monstrous .373. Pitchers tried to pitch around him – he walked 109 times – but he knocked around enough of them to beat Detroit’s Harry Heilman by 31 points for his first MVP Award.

What about Ruth? He hit 60 home runs in ’27. At the time, a player could not be nominated for future MVP Awards if they had already won one. That’s the reason why you will not see Babe Ruth’s (1923 MVP) name among the 1927 candidates. It might have made for an interesting MVP vote, since in addition to his 60 home runs, Ruth also collected 165 RBI and put together a 1.258 OPS. It’s not inconceivable to think the two Yankees stars could have split the vote, with neither capturing the award.

The RBI Man

Fans and Sabermetricians tend to scoff at a player’s runs batted in (RBI) total these days. But, you can’t scoff when a hitter is knocking in 130 to 184 runs a year. Gehrig matched his ’27 total of 173 RBI in 1930, and then set the AL record (which still stands) a year later when he knocked in 184.

The rules for the AL MVP had changed by 1931, and remarkably, Gehrig only finished second after leading the league in home runs (46 ), RBI, hits (211), runs (163), and total bases (410). He added 31 doubles, 15 triples, and walked 115 times while striking out only 56 times. There is no hitter today – whether it be Miguel Cabrera, Mike Trout, Bryce Harper, etc. – that could put up comparable numbers.

Over the next six seasons, Gehrig averaged 148 RBI and topped 150 RBI seven times in his career.

Old Reliable

Before the Yankees’ Tommy Henrich earned the nickname, Gehrig could have been referred to as “Old Reliable”. Obviously, durability was a big factor. His 2,130 game streak lasted from June 1925 through April 30th, 1939, when his illness had weakened him too much to play. The stretch from 1927 through 1937 were Gehrig’s best years.

In those 11 seasons, Gehrig’s average slash line was .350/.459/.659 (1.117 OPS) with 39 HR and 154 RBI. He also averaged 39 doubles, 11 triples, 380 total bases and 113 walks/53 strikeouts. He won a second MVP Award in 1936 and finished in the Top-5 eight times. Had it not been for the rules prohibiting multiple nominations, he certainly would have finished in the Top-5 in voting in all 11 years.

Gehrig topped the league in games played seven times, plate appearances twice, home runs on three occasions, RBI five times, runs scored four times, and three times led the AL in walks. He won a batting title in 1934, the sole season in his career when he also had the top on-base and slugging percentages and the top OPS.

He had 200 or more hits seven times and held the team record of 2,721 career hits until Derek Jeter passed him in 2009. Gehrig finished his career seven home runs shy of 500 and five RBI short of 2,000. The All-Star game began in 1933, so Gehrig was a member of the AL team seven times, though the final selection was an honorary appointment. He also captured six World Series titles and seven pennants.

The End

Gehrig’s legacy is not defined by the disease that bears his name, but it did take his life. (There have been theories in recent years that Gehrig may have suffered from an ALS-associated ailment, not ALS itself.) The “pride of the Yankees” started feeling the effects of the disease during the 1938 season. Doctors couldn’t figure out what caused his fatigue and aches and pains. He managed to hit 29 home runs and drove in 114 runs, but he batted just .295 and his OPS dipped below 1.000 for the first time since the ’26 season. He still played in every game.

The Final Goodbye

On July 4, 1939, in front of a packed Yankee Stadium, Lou Gehrig said goodbye. Fans, dignitaries, current and former teammates wept openly as Gehrig called himself “…the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” Among those on the field was Ruth, with whom Gehrig had had a falling out years earlier. The Yankees retired Gehrig’s number 4 and lavished him and his wife Eleanor with gifts. That December, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

On June 2, 1941, approximately 16 years after the start of Gehrig’s iron man streak, he passed away. Born Heinrich Ludwig Gehrig, he died 17 days before his 38th birthday.

We remember his illness and his speech, but we should always remember what an incredible baseball player he was. That is what truly defined him to the public.