A Tale of Two Sluggers

When the MLB trade rumors start up this summer, Todd Frazier will be one of the biggest names bandied about. The established All-Star, power-hitter, and good clubhouse guy will be a free agent after the 2017 season. In contrast, Chris Carter feels fortunate to even be on any Major League team right now after the Milwaukee Brewers released him in early December and he sat without a contract for six weeks.

Frazier is a player that, in theory, every team wants. He’s a former first-round draft pick (34th overall selection in 2007), while Carter waited until the White Sox finally selected him in the 15th round two years earlier. By contrast, Carter has struggled to find a permanent home despite hitting a home run every 15.2 at-bats. A large part of the reason is that Carter strikes out every 2.6 at-bats. But, if you look more closely, there really isn’t too much of a difference between the 2017 versions of the two players.

Frazier made $8.25MM last season and will earn $12MM this season. Though the market has changed for some players, Frazier is likely to land a multi-year deal with an average salary higher than what he’ll earn this year.

Carter, meanwhile, will be arbitration-eligible for the first time after this season and hopes to land a long-term deal when he’s eligible for free agency in 2019. He settled for a one-year $3.5MM deal with the Yankees in early February. With the Yankees relying on Greg Bird at first base and Matt Holliday at DH, there is no guaranteed playing time for Carter.

Chicks Don’t Dig the Long Ball as Much

Part of the misconception between the pair has been caused by the evolution of the game in the last 20 years. During the steroid-fueled home run era from the mid-1990’s to the mid-2000’s, the home run was king. In 1998, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa battled to break Roger Maris‘ single-season home run record. Three years later, Barry Bonds eclipsed McGwire’s 70 home runs with 73. Guys were hitting 40-50 home runs a year like they were playing a video game.

It appeared like Commissioner Bud Selig ignored the steroid issue since the fans that had walked away from the game as a result of the 1994 players strike and World Series cancellation were returning. MLB and Nike promoted the hell out of home runs, including the famous Greg Maddux–Tom Glavine commercial that was all about how “chicks dig the long ball.”

But, the game of baseball has changed in the last decade. As far as power hitters go, it hasn’t totally changed for the better. Gone are the muscle-bound 50-home run, 130-RBI per year batters. In their place came players who hit 35-40 home runs, but struck out 180-210 times a year. This was the opposite strategy of the high on-base percentage “Moneyball” approach; teams placed a premium on players that hit home runs and made less contact with the baseball.

More recently, baseball has started to move away from the all-or-nothing approach to hitting. Players like Carter and Mark Reynolds are bouncing around the league due to their lack of contact.

I’m Not a Home Run Hitter

“I’m not really a home run hitter” or “I’m not a true slugger.” How many times have we heard a home run hitter tell that to a member of the media in the last five years? Curtis Granderson immediately comes to mind. You are a bona fide home run hitter/slugger when you put together back-to-back 40-home run seasons as Granderson did in 2011 – 2012 with the Yankees.

Earlier in his career, Frazier was thought of as a well-rounded hitter, but he’s always had a power bat. He spent his first five Major League seasons with the Cincinnati Reds before a trade sent him to the Chicago White Sox prior to last season. In his final two seasons in the Great American (Bandbox) Ballpark in Cincy, he averaged 32 home runs. Last season, his first with the White Sox, he blasted a career-high 40 home runs. He also won the 2015 Home Run Derby at the All-Star game and was the runner-up to Giancarlo Stanton last year.

The price for the increase in his power has been steep. He hit a career-low .225 (with a .302 on-base pct.) in 2016 and struck out a career-high 163 times. When Frazier didn’t hit a home run, his Isolated Power (Slugging pct. minus batting average) was just .239. A hitter should also drive in more than 98 runs (Frazier’s output last year) when he knocks 40 out of the park. This has also been a growing trend in baseball – more home runs, less RBI per HR.

Frazier’s rookie season in 2012 and his 2016 season can be seen in the spray charts that follow. The third baseman’s 2016 spray chart on the right shows that all but one of his home runs and his hardest hit baseballs are predominantly to the left side of the field. When he tries to hit to the opposite field it usually turns into a pop out/fly out. While I wouldn’t classify him as a dead pull hitter, he’s very close to being one.

By comparing Frazier’s rookie season (the spray chart on the left), to last season, you can see the change in Frazier’s approach. Granted, it was in a different ballpark, but he used the entire field much more than he does today. As a result, his slash line in 2012 (.273/.331/.498) was much better than it was last year (.225/.302/.464).

Source: FanGraphs |

Source: FanGraphs |

Carter’s breakout year came in 2009 when, after a trade to Oakland (via another offseason deal to Arizona), he belted 39 home runs for Class-A Stockton. After 16 home runs in 67 games in 2012, Carter got the chance to play full-time in 2013. But, not before yet another offseason deal, this time to Houston.

Despite the potential he showed for the Astros with 29 home runs and 82 RBI, his numbers were dwarfed by a league-leading 212 strikeouts and a nothing-special .770 OPS. Carter improved the next year with a 37-HR, .799 OPS, 182-K follow up, but his rollercoaster ride continued in 2014.

In 391 at-bats, Carter was limited to 24 home runs and batted just .199. His saving grace was the free passes that put his on-base percentage over .300. He was non-tendered by the Astros and signed with the Brewers for 2016. And, this is where the Frazier – Carter convergence is most clear.

Before looking at that, let’s take a quick look at Carter’s spray charts from his first full year in 2013 on the left and his 2016 season on the right. The first thing that jumps right out at you is that Carter used much more of the field than Frazier. Carter also had the disadvantage of playing in Oakland, a pitcher’s park with a ton of foul territory that turns pop-ups that normally land in the seats into outs. Unlike Frazier, Carter’s home runs were to all parts of the field when he got a chance to play regularly. Last year, he still hit the ball out, ranging from right-center field to the

Unlike Frazier, Carter’s home runs were to all parts of the field when he got a chance to play regularly. Last year, he still hit the ball out, ranging from right-center field to the left field line. Carter’s slash line was slightly better in 2016, but that was only because of his increase in slugging percentage.

Source: FanGraphs |

Source: FanGraphs |

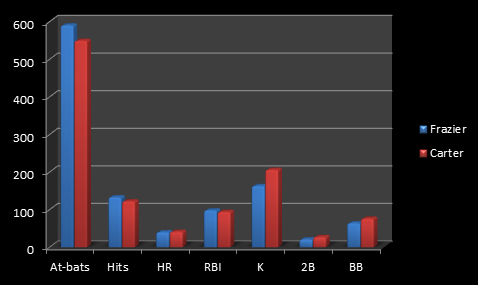

In the first chart below you can see just how similar Frazier’s and Carter’s 2016 offensive seasons were when it came to power numbers, RBI, and strikeouts.

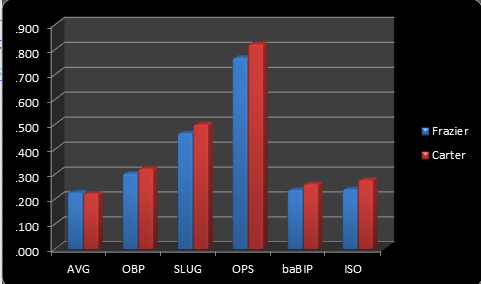

In this second chart, you can see that Carter’s numbers were very similar to Frazier’s, and in some case, actually better. Specifically, his OPS, ISO, and batting average on balls in play (baBIP) topped Frazier’s numbers.

So, what happens this season? Barring injuries and/or ineffectiveness by Bird or Holliday, Carter won’t get anywhere near the number of at-bats he’s averaged in the last four years. Frazier, who is currently battling an oblique injury, will likely get dealt to a contender down the stretch.

And, after the season? Frazier will get his big money deal and Carter will probably have another long wait looking for a one-year deal. This despite the fact that right now they are basically the same player when they step into the batter’s box.