He plays golf each morning and hoops each evening, and by 10 p.m. he is nestled in bed with his Nintendo control pad. He makes Roy Hobbs look like John Kruk, and he makes you wonder if you’re missing something: A guy this sweet has to be hiding some cavities.

– Sports Illustrated, July 8, 1996

Alex Rodriguez burst onto the baseball scene in 1996, hitting .358 with 36 homers and 123 RBI in 146 games, placing him second in the MVP voting and giving him his first of an eventual 14 All-Star nods. He was on his way towards becoming the greatest player of all-time; it was almost certain. Scouts marveled at him, they couldn’t find anything wrong in his game, in his head. His baseball IQ was off the charts, he was a quick learner. He was destined for greatness, for immortality.

After playing in Seattle, he cashed in on a mega-deal with Texas, becoming the highest paid athlete in history. He put up three legendary years in the Lonestar State. Then came the move to the Big Apple.

Flash forward almost two decades removed from Seattle. It wasn’t supposed to turn out this way.

“I’m pretty excited. This is a big, big one,” Yankees owner George Steinbrenner said after the Yankees acquired Rodriguez in February of 2004.

It was a big one. Perhaps too big. It changed the course of baseball history, actually. He was almost a member of the hated Boston Red Sox when the deal was nixed by Commissioner Bud Selig due to the large amount of money changing hands between Texas and Boston. The Yankees slipped in, and traded Alfonso Soriano and infielder Joaquin Arias for him. The rest is history.

He was supposed to be the guy to break the home run record the right way. The clean way. After all, he arrived in the Bronx with a career line of .308/.382/.581 with 345 home runs and 990 RBI – all at the age of 27. He was supposed to deliver championships to New York after a three-year hiatus – an eternity in Yankee years. He was supposed to become another player in the long line of beloved legendary Yankee sluggers and Hall-of-Famers. Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Berra, Mantle, Jeter… Rodriguez. After nine years of headaches, heartaches, hip-aches the A-Rod era in New York can be summed up in one word:

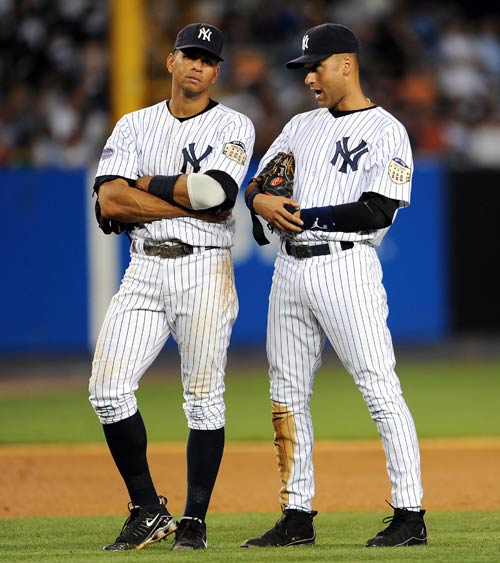

From the beginning, A-Rod was almost destined to never be accepted as a “true Yankee.” Here came this $252 million man, with his private jet and the gaudy numbers, into Jeter’s territory, Jeter’s city.. Jeter’s team. Especially after the disparaging comments A-Rod made about Jeter some years earlier in an Esquire article, Yankee fans were never warm towards the superstar. In fact, those comments helped turn the solid relationship between the two shortstops cold.

From 2004 up until now, he’s had multiple on the field controversies and off the field tabloid bombshells. From the Arroyo glove-slap to the opt-out during the World Series. From Hip surgeries one and two to steroid scandals one and two and throwing baseballs to blondes in the stands, A-Rod never could get out of his own way in New York – a bad thing since the microscope is always on you. He wanted to be liked and accepted; he wanted the unconditional support like Jeter had.

He was so insecure about himself and his image that he took to PEDs as a crutch. But he didn’t need them. Ask anyone around baseball, and they’ll tell you Rodriguez is the hardest working player in the game. Focused and determined with attention to detail, he was the complete package. He had won half the battle with his preparation alone, and his talent completed the puzzle.

That’s what makes his story frustrating, tragic and almost sympathetic. One of the hardest questions to face in sports is when you ask “what could have been?” With A-Rod, that question will likely run through his head for the rest of his life. He was going to be the best we ever saw; the best to ever put on a glove and swing a bat in the history of the game. He threw it all away, and he has no one to blame but himself. We gave him a second chance and believed him after he said in ’09 he only used steroids for a portion of his career. It’s beginning to make sense that maybe he used for longer than that. His nine years in New York feel empty, and now so does a career that was once labeled as immortal. And that’s sad.

“I still feel like someone’s going to pinch me and wake me up,” Rodriguez said at his introductory press conference in 2004. So there he was at the podium, donning pinstripes for the first time. An insecure guy with the richest contract in sports history and a world of talent who has the insatiable need for everyone to like him. Oh, and he plays in New York City; bad combination.

What seemed like a warm fantasy to Rodriguez then must feel like a cold reality now. Even though he put up one of the greatest seasons we’ve ever seen in 2007 and one of the greatest postseasons of all-time that ended in a championship in ’09, which at the time, solidified his career, it won’t be remembered. Much like Barry Bonds, baseball will choose not to remember him when this is all settled.

But for now, A-Rod will fight this thing to the end. He has nothing to lose, except maybe the $100 million he’s owed by the Yankees plus countless legal fees to his team of lawyers, which he no doubt can afford. He’s facing the biggest non-gambling banishment since Shoeless Joe Jackson. This is historically bad.

A-Rod can’t do anything now to change people’s perception of him as a baseball player and as a human being. No home run from today forward will help erase memories of these past nine years in pinstripes, or 17 years of a career. No interview or public statement will change his legacy. No appeal process and verdict will sway a nation that’s labeled him a villain and a criminal.

No matter what he does, he won’t be remembered as a “good” person, like he wanted to be back in 1996 – the year he put himself on the map; the year we first laid eyes on what we thought was greatness.

“My mom always said, ‘I don’t care if you turn out to be a terrible ballplayer, I just want you to be a good person,” says Rodriguez. “That’s the most important thing to me. Like Cal or Dale Murphy, I want people to look at me and say, ‘He’s a good person.’ “