My first memories of watching baseball are from the 1996 postseason. I was 8 years old.

In my house, the games would be on the TV in the living room. I would plop a sleeping bag in the middle of the floor in case I felt the urge to fall asleep, but the action on the television kept my heart racing a mile-a-minute. My dad, rarely sitting still, would pace back and forth often times having to step over me.

The voices of Joe Buck and Tim McCarver that echoed throughout my house talked about Joe Torre finally reaching the World Series after a lifetime of regular season games and a young – but poised – shortstop named Derek Jeter.

The Yankees were on a Cinderella-run thanks to their bullpen, which would surely come to an end against the big, bad Braves. Atlanta was the team of the decade (oh, how that would change) looking to repeat as world champs.

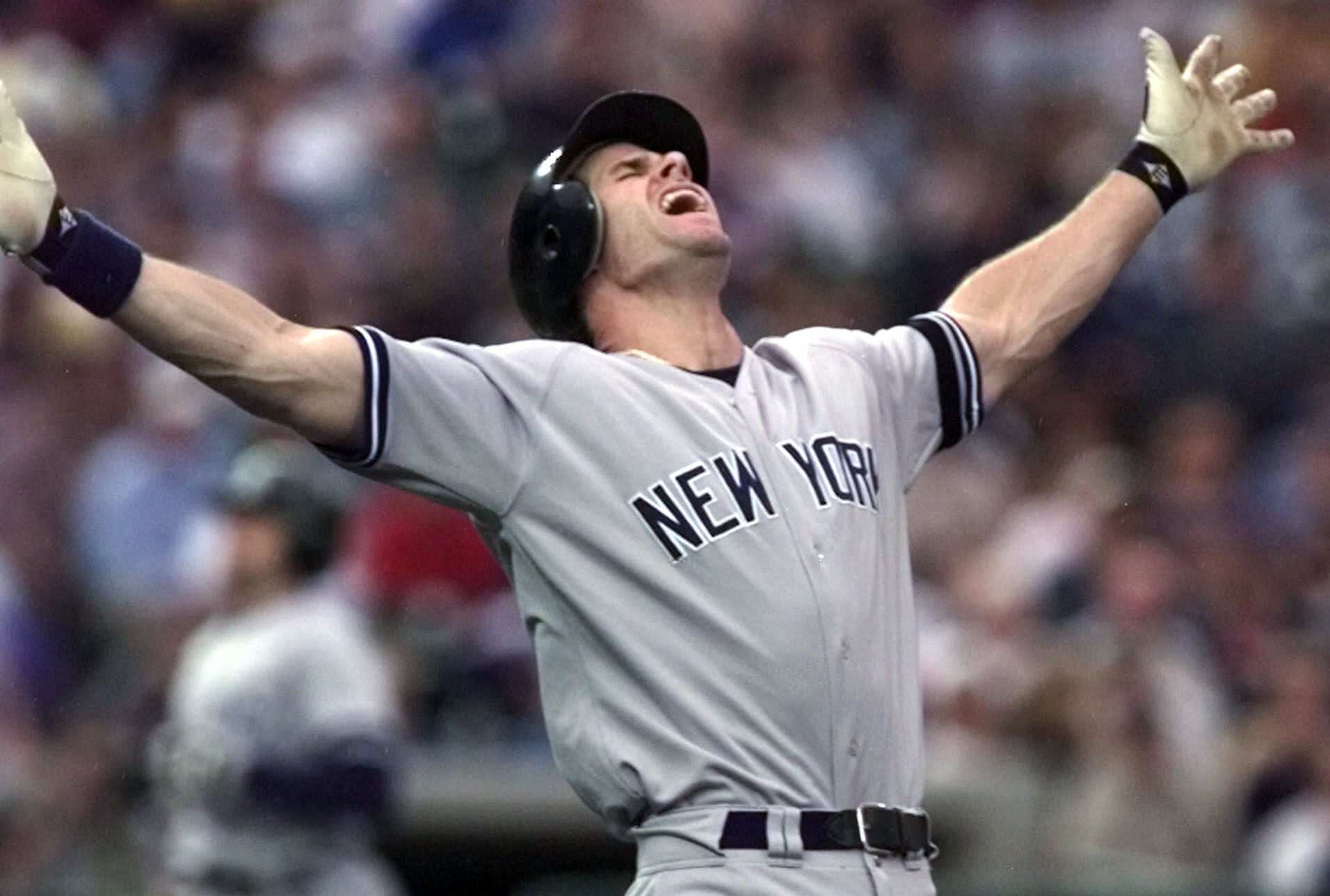

The announcers also discussed the Yankees hobbled right fielder who was battling a hamstring injury. The 1994 batting champ had been dropped from his usual third spot in the order after a horrendous ALDS. The injury, which prevented Paul O’Neill from using his lower half, was taking its toll but O’Neill didn’t use it as an excuse.

As Buck and McCarver were saying these words, O’Neill lined a ball deep down the line that briefly disappeared into the dimly-lit right field corner as it short-hopped the wall. Paulie gingerly jogged into second base for an easy double and a rally was born. He would later score on a triple by Joe Girardi that almost brought Yankee Stadium crumbling to the ground.

It was Saturday, October 26, 1996 – Game 6 of the World Series.

On November 3, 1992 the Yankees traded Roberto Kelly to the Cincinnati Reds for Paul O’Neill. Looking back, it has to be one of the best trades in franchise history.

O’Neill, an Ohio native playing for his “hometown” Reds, averaged .259/.337/.431 from 1987-92 – modest numbers when you compare them to the All Star-caliber .303/.377/.492 he averaged in pinstripes.

During his first 6 seasons in New York, O’Neill placed in the top-15 of MVP voting 4 times and won the 1994 batting title with a .359 average. He became a fan-favorite, largely because of his on-field production and reputation of being a clubhouse leader, but also because he lived and died with every single pitch.

As fans, we want our players to care. First and foremost, they must produce, but they also need to show that the game they’re playing for millions of dollars means more to them than our nine-to-five job does to us. It may sound naïve, but it’s the reality.

Paul O’Neill embodied everything we, as New York Yankees fans, wanted in a ballplayer. He was tough, played injured, didn’t make excuses, led, treated winning like it was life, and – most importantly – succeeded.

When he grounded out it was like we were grounding out. The disgust on O’Neill’s face showed that he truly cared about the game us fans watched every night for entertainment.

The majority of players I’ve watched since 1996 do not show much emotion. For every Paul O’Neill there are 100 JD Drew’s, who had the same feeble-minded stare on his face whether he struck out or hit a grand slam. Robinson Cano, one of the best all-around players I’ve ever seen, treated grounding out the same way we’d treat not responding to an email on time – no big deal. Fans noticed.

Cano, like many other players, take the approach that the season is a marathon not a sprint. That another chance will come in 8 short batters. But not Paulie. I remember a quote from Joe Torre who said O’Neill expected to get a hit every time up which is why he got so angry when he didn’t come through.

You can make the argument that shtick gets old. Bashing a Gatorade cooler on June 10th because you went 0-for-4 is ridiculous since it’s just 1 of 162. If you treat a June game like it’s a game 7 then how can you possibly elevate yourself when October actually arrives?

A player that used to get compared to O’Neill was Kevin Youkilis – not the most talented player but he showed plenty of emotion and meant a lot to Boston’s success. Eventually Sox players and fans tired of Youk’s act when he would slam his helmet after making out in a game they were leading by 6. The difference, by my calculation, was that Youk’s outbursts tended to come from a place of selfishness, whereas O’Neill’s were more genuine – he was angry because he let the team down. Perhaps I’m biased, but I do not know of any Yankees player or fan who ever got tired of Paulie’s act.

It’s the reason that O’Neill has a plaque in Monument Park. It’s the reason why the YES broadcasts with O’Neill are usually the most interesting and why the Stadium erupts whenever he’s shown on the big screen. It’s the reason why O’Neill’s number 21 has not been worn since he last played a game, 15 years ago. And finally, it’s the reason why I – as I’m sure many people my age – picked number 21 in little league.

Two hours after lining that double into the right field corner and scoring the game’s first run, Paul O’Neill toppled over the celebratory human pile that formed on the mound at Yankee Stadium. The Yankees had won the 1996 World Series, their first since 1978 and first of four with O’Neill.